Multimodal Reasoning in Math Geometry

Vision-language models struggle with geometric reasoning, particularly fine-grained spatial relations in diagrams. We introduce an iterative Planner → VQA → Belief-state reasoning pipeline that actively requests missing geometric facts before committing to answers. Without additional training, our GPT-4o pipeline doubles baseline description quality and achieves 40% accuracy with 4.00 CoT reasoning score, while the open-weights Qwen variant reaches 34% accuracy, proving that targeted visual querying drives geometric reasoning performance.

Role

Skills & Tools

Work Responsibilities

- Conducted an extensive survey of multimodal math/geometry research and defined the problem of geometric reasoning in VLMs, highlighting common perception–reasoning failures.

- Co-developed a planner–VQA–reasoner pipeline that actively queries diagrams and separates perception from reasoning, enabling more accurate geometric fact extraction and logical consistency.

- Demonstrated that a GPT-4o + pipeline setup outperformed GPT-4V in description faithfulness (+16%) and reasoning coherence (+54%), showing the effectiveness of targeted querying compared to end-to-end VLMs.

- Performed systematic experiments and error analyses, diagnosing whether errors arose from misperception or faulty reasoning, and providing guidance for future model design.

Abstract

We study whether vision–language models can truly reason about geometry rather than merely label diagrams. On a MathVerse subset of multiple-choice problems, eight baselines—ranging from text-only LLMs to state-of-the-art VLMs—still struggle with fine-grained spatial relations.

We introduce an iterative pipeline that alternates planning questions, VQA fact extraction, and belief-state reasoning. Without additional training, the full GPT-4o variant doubles baseline description quality and raises accuracy to 40%, while an open-weights Qwen version reaches 34%.

Results suggest that targeted visual querying, not larger language models alone, is the critical driver of geometric reasoning performance.

Introduction and Problem Definition

Multimodal technologies have demonstrated remarkable potential in tackling complex real-world tasks, leveraging their powerful capability to integrate visual and textual information. Inspired by this emerging trend, our team was intrigued by the possibility of effectively applying these technologies within the traditionally challenging domain of mathematics. Specifically, we asked: could the rapidly evolving vision-language models (VLMs) yield breakthrough results when applied to geometric mathematical problems?

To clarify our research motivation, we first examined recent developments in mathematical reasoning technologies. Over the past few years, large language models such as GPT-3 and GPT-4 have made significant strides in algebra, logical reasoning, and solving complex text-based problems, exemplified by their excellent performance on benchmark datasets like GSM8K. These advancements provided essential insights and encouragement for further research. However, our curiosity grew regarding model performance when reasoning tasks expand beyond pure textual logic, involving visual and spatial interpretation of images.

Consequently, our team decided to focus specifically on geometric reasoning tasks within mathematics. Unlike typical text-based reasoning problems, geometry requires precise perception and reasoning about detailed structural and spatial relationships within images—such as points, lines, surfaces, geometric shape combinations, segment lengths, angle measurements, parallel or perpendicular relationships, shapes' containment and partitioning, overall symmetry, and spatial layouts.

Recent advancements in vision-language models, notably GPT-4V and LLaVA-7B, have demonstrated robust general visual comprehension abilities, seemingly offering ideal solutions for this task. However, upon deeper literature review, we discovered that even these state-of-the-art models exhibit significant limitations and shortcomings in specific geometric image reasoning tasks, particularly in handling precise spatial details.

Further investigation into possible reasons for these shortcomings led us to examine popular geometric datasets such as MathVerse and Geometry3K. We found that while current datasets commonly provide geometric images, question texts, choices, and answers, they lack detailed, explicit, and structured geometric image descriptions. This absence of descriptive context may significantly limit the models' ability to thoroughly understand image information, thus impairing their performance on detailed geometric reasoning tasks.

Based on these findings, we clearly defined our research goal: If we proactively generate and provide explicit, structured descriptions of geometric images, can this effectively enhance the performance of vision-language models on geometric reasoning tasks? To verify this question, we explicitly formulated two core hypotheses.

Research Hypotheses

Caption Benefit Hypothesis

Providing detailed and explicit image descriptions can significantly enhance model accuracy on geometric problems compared to using only raw images or text.

Task-Focused Caption Hypothesis

Descriptions specifically tailored to focus on visual features directly related to geometric problem-solving (e.g., specific angles, segment relations) will more effectively improve model reasoning capabilities and overall problem-solving performance compared to general image descriptions.

Building on this motivation, our final solution extends the classic perception-reasoning split into an iterative three-component loop—planning → targeted visual question answering → belief-state reasoning—so that the system can actively request missing geometric facts before committing to a final answer.

Contributions

To achieve and validate these hypotheses, our project clearly offers four main contributions:

Proposing and validating a novel multimodal geometric reasoning pipeline

We explicitly divided the geometric reasoning task into two distinct stages: Perception Stage (utilizing advanced vision-language models such as GPT-4V and Qwen-VL to generate structured descriptions) and Reasoning Stage (combining generated detailed descriptions with problem texts to enable final reasoning and answer generation by large language models).

Introducing a task-oriented structured image description generation strategy

Our method addresses the lack of structured image descriptions in existing datasets by clearly instructing the model-generated descriptions to focus specifically on visual features directly relevant to problem-solving, thereby enhancing the model's precise understanding of geometric details.

Conducting comprehensive baseline comparative analyses

We systematically compared eight different model combinations and strategies, ranging from pure text models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4o, Mistral 7B) and simple multimodal fusion models (CLIP+GPT-3.5, BLIP+GPT-3.5) to advanced vision-language model combinations (GPT-4V, Qwen-VL, InternLM).

Providing clear and in-depth experimental insights

By analyzing Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning scores, description generation scores, and their combined overall accuracy, we conclusively demonstrated that detailed image descriptions have a significant positive impact on overall geometric reasoning accuracy. Our experimental design allows us to identify whether errors originate from the perception or reasoning stage.

Related Work and Background

Related Datasets

Several recent works have advanced the field of mathematical and geometric problem-solving using multi-modal models. The MATH dataset provides a large-scale benchmark focused on text-based mathematical problem-solving, while MathVista expands this space by evaluating multi-modal models on visual math problems that combine diagrams with textual descriptions.

GeoEval introduces a specialized benchmark for geometric reasoning, designed to test the ability of the models to interpret complex figures and solve geometry questions. MathVerse further investigates whether multi-modal LLMs can truly "see" and reason over diagrams, revealing important gaps between image understanding and symbolic reasoning.

Prior Work

To address these challenges, a variety of models have been proposed. G-LLaVA adapts multi-modal LLMs to geometric problem-solving by integrating visual and textual features, while Inter-GPS introduces formal symbolic reasoning pipelines to enhance interpretability and solution accuracy.

UniMath aims to build a foundational multi-modal mathematical reasoner across different modalities and task types. ChatGLM-Math focuses on improving text-based math problem-solving through a self-critique pipeline, showing that even unimodal LLMs can benefit from better reasoning structures.

Dual-Reasoning Geometry Solver (Dual-GeoSolver) explores a dual-reasoning approach inspired by human problem-solving strategies, emphasizing the importance of both visual and symbolic understanding. Reason-and-Execute prompting method proposes a framework for breaking down complex geometry questions into executable steps to enhance structured reasoning.

More recently, GeoX presents a unified pretraining framework that jointly formalizes visual diagrams and symbolic descriptions, enabling better alignment between vision and language for geometric problem-solving. Similarly, Geo-LLaVA extends the capabilities of multi-modal LLMs by applying meta in-context learning and retrieval-augmented training on solid geometry datasets, achieving state-of-the-art results on benchmarks like GeoQA and GeoMath. GeoGPT4V explores synthetic generation of geometric figures to augment training and evaluation data, further pushing the boundaries of geometry-focused multimodal learning.

Unimodal and Multimodal Baselines

Baseline models in this domain often start from unimodal language models such as ChatGLM-Math or solvers evaluated on the MATH dataset, providing a reference point for text-only problem-solving capabilities.

In parallel, foundational vision-language models like ViLT and BLIP-2 have laid critical groundwork for multi-modal learning, evaluated through image-text retrieval and captioning tasks with metrics like Recall@1, BLEU, and CIDEr. GPT-4V builds upon these efforts, expanding vision-language capabilities into more complex reasoning domains, including math and science-related tasks.

Relevant Techniques

Relevant techniques have also evolved alongside model architectures. Multimodal Chain-of-Thought reasoning introduces structured multi-step prompting to enhance complex problem-solving across visual and textual modalities. Compositional Chain-of-Thought further explores how reasoning steps can be broken down and composed dynamically, improving both flexibility and generalization in multi-modal tasks.

In their paper "Beyond Lines and Circles" the authors investigate persistent challenges in LLM geometric reasoning, emphasizing that current models still struggle with deep understanding of spatial relations. Finally, Mavis leverages automated visual instruction tuning to construct high-quality training data at scale, addressing data scarcity issues in mathematical vision-language tasks.

Together, these datasets, models, baselines, and techniques form a rapidly growing research landscape focused on advancing multi-modal reasoning, particularly for challenging domains like mathematical and geometric problem solving.

Task Setup and Data

The primary task of our project is to solve mathematical geometry reasoning problems by integrating textual and visual information to accurately answer multiple-choice questions (MCQs).

Dataset

We utilize a subset of the MathVerse dataset, which includes 750 training samples and 250 testing samples. These samples are categorized into four versions based on the distribution of information across modalities:

Text Dominant

Provides detailed textual descriptions with supporting images.

Vision Dominant

Images contain the majority of critical information, supplemented by minimal text.

Text Lite

Very brief textual information, with images as the main information carrier.

Vision Only

Solely visual information without any text.

Task Design: Two-Stage Process

In our task design, the geometric reasoning process is explicitly divided into two stages:

Perception Stage

Vision-language models (e.g., GPT-4V, Qwen-2.5-VL) are employed to generate structured descriptions of geometric images. These descriptions focus on extracting key entities and relationships, such as points, lines, angles, and spatial configurations.

Reasoning Stage

The structured image descriptions are combined with the original question texts and passed into large language models (e.g., GPT-4o) for chain-of-thought (CoT) based reasoning and final MCQ answer generation.

This two-stage separation enables a clearer analysis of bottlenecks and strengths within perception and reasoning individually.

To further reduce residual uncertainty, our experiments also evaluate an iterative variant that loops through "Planner → VQA → Belief-state" cycles (maximum 3 rounds) before entering the final reasoning stage. This setting mirrors the full pipeline and allows us to quantify the benefit of active information acquisition.

Baselines

To systematically evaluate the impact of different modality input strategies on geometric reasoning tasks, we designed and tested eight baseline models, covering three main categories: unimodal reasoning, simple multimodal fusion, and competitive multimodal understanding. These baselines establish a solid foundation for subsequent model comparisons and performance analysis.

Unimodal Text-Dominant Baselines

We first assessed the reasoning performance using text-dominant input, evaluating the following large language models:

GPT-3.5 (Text Dominant)

GPT-4o (Text Dominant)

Mistral-7B (Text Dominant)

In this setting, the models receive question text, with any necessary visual information embedded within the text description. This enables us to benchmark the maximal reasoning capabilities achievable without detailed visual input and quantify the added value of multimodal integration.

Simple Multimodal Fusion Baselines

We then explored basic multimodal strategies involving direct feature fusion, employing two modeling approaches:

GPT-3.5 + CLIP

CLIP is used to separately extract embeddings from images and text, followed by linear mapping fusion, with the resulting fused representation passed into GPT-3.5 for answer generation.

GPT-3.5 + BLIP

BLIP generates textual descriptions from images, which are concatenated with the question text and input into GPT-3.5 for reasoning.

These simple fusion baselines assess the effectiveness of low-cost visual-text integration approaches for geometric reasoning tasks.

Competitive Multimodal Baselines

To further explore the potential of vision-language models in complex reasoning, we evaluated three advanced multimodal understanding methods:

GPT-3.5 + InternLM-XComposer2

InternLM-XC2 generates joint visual-textual descriptions, which are combined with the problem text and passed to GPT-3.5 for final reasoning.

GPT-4V

GPT-4V directly processes combined image and text inputs, producing detailed visual understanding and logical reasoning steps.

Qwen-2.5-VL

Qwen-2.5-VL performs end-to-end joint visual-textual reasoning, directly generating final answers.

In all baseline experiments, the final MCQ answer is consistently generated by GPT-3.5 to control for differences in language model reasoning ability and ensure fair comparison across different input strategies. Through the systematic comparison of these eight baselines, we provide an in-depth analysis of the contributions of visual information at various stages of feature extraction, description generation, and logical reasoning, forming a strong empirical basis for our proposed modeling improvements.

Proposed Model

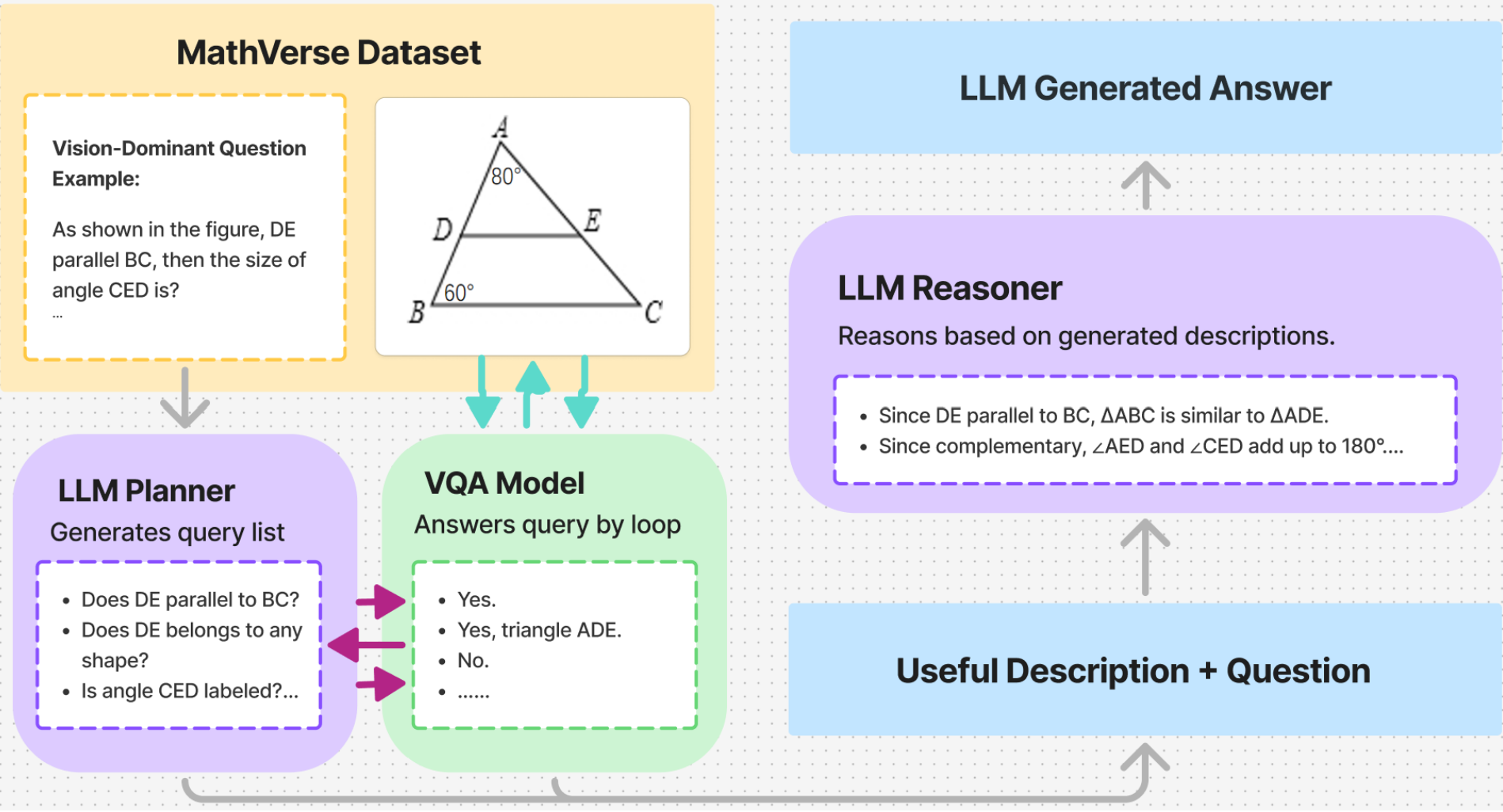

Our proposed model consists of three main parts. Essentially, Planner asks the initial and follow-up questions, VQA reads the image, Reasoner finishes the problem.

Figure 1: Proposed pipeline structure

Pipeline Stage Description

A more detailed description of each part is as such:

| Stage | Component | Input it receives | Output it produces | How the output is used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Planner LM | Plain question text; Previous Q/A log (empty in round 0) | Up to 3 short follow-up queries, one per line. If none are needed, returns "NONE". | Each query is sent, one by one, to Stage 2. |

| 2 | VQA model | Query text asking for relevant information in diagram; Original diagram image | A short answer ("Yes, ABC is a triangle.", "60°", "UNKNOWN", etc.). | The pair Qn/An is appended to the belief-state string. |

| 3 | Belief-state builder (simple Python code) | All previous Q/A pairs; New Q/A from Stage 2 | Belief-state string—a newline-separated transcript (e.g., "Q1: ... A1: ... Q2: ... A2: ..."). | The updated string is passed back to Stage 1 for the next round and to Stage 4 once looping stops. |

| 4 | Reasoner LM | Final belief-state string; Original question text | A two-part response. Reasoning Step: short chain of logic in prose; Final Answer: one option letter (A/B/C/D). | Final Answer is the pipeline's prediction for accuracy grading. |

Loop Control

The planner, VQA model, and belief-state builder (Stages 1 → 2 → 3) repeat until either:

- The planner determines the current belief-state string contains enough information and thus outputs NONE, or

- The hard cap of rounds (currently set to 3) is reached.

After that, Stage 4 runs once and the pipeline ends.

Model Configurations

Here are a table of different choices of models for each part:

| Pipeline tag | Planner LM | VQA model | Reasoner LM |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | Mathstral-7B-v0.1 | InternLM-XC2-VL-7B | Mathstral-7B-v0.1 |

| P-2 | Qwen-Chat-7B | Qwen-VL-Chat | Qwen-Chat-7B |

| P-3 | GPT-3.5-Turbo | GPT-4o-VQA | GPT-3.5-Turbo |

| P-4 | GPT-4o (text) | GPT-4o (vision) | GPT-4o (text) |

Table 2: Planner, VQA, and Reasoner models used in each version of pipeline.

Loss Functions

None are needed.

All models are frozen; gradients are not computed or updated. We only do forward passes.

Yet there is a logical loss being minimised at run-time:

- Planner's implicit loss to minimize number of model generations / API calls – ask as few extra questions as possible while still solvable. We let the model decide when to stop, so this loss minimization is implemented by prompt tuning, asking the model to return "NONE" when no new information seems useful.

Changes to Training Data

Our pipeline didn't require any training, thus no extra images, labels, or fine-tuning examples are added.

Filtering to question_type = "Vision Dominant" is the only data step. This is because in this category much of the geometric detail (right-angle marks, parallel ticks, labeled lengths, etc.) appears only in the diagram, while the text is deliberately minimal. By filtering to this subset, we guarantee that:

- Stage 2 (VQA) is essential. Without the extra queries the problem is unsolvable.

- The evaluation can measure the quality of our query-planning and vision reading rather than pure text reasoning.

The belief-state string is a temporary text, thus not stored back to the dataset.

Hyperparameters and their Effects

| Name (in code) | Default | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| MAX_ROUNDS | 3 | Upper bound on LM↔VQA cycles. 2 is faster-but-weaker; 4 adds cost in API calls and wait time with <0.2 pt gain in description quality score. |

| temperature (Planner) | 0.2 | Keeps questions short and focused. |

| max_new_tokens (Planner / Reasoner) | 128 / 200 | Prevents truncation. |

| do_sample=False in VQA | – | This forces greedy decoding, ensures no random token picking, so angle values and simple "Yes/No" answers can hopefully stay fixed and repeatable instead of drifting. |

| float16 / bfloat16 | – | Reduces VRAM, helps the model to fit in L4/A100 GPU's. No measurable accuracy loss. |

Table 3: Hyperparameters and their effects in the pipeline.

Overall Performance Comparison

| Methods | Accuracy | CoT Reasoning | CoT Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline models – unimodal (text-only LM) | |||

| GPT-3.5-turbo (Text) | 0.22 | – | – |

| GPT-4o (Text) | 0.58 | – | – |

| Mistral-7B (Text) | 0.18 | – | – |

| Baseline models – competitive (Reasoner LM + Vision model) | |||

| GPT-3.5 + BLIP | 0.13 | – | – |

| GPT-3.5 + CLIP | 0.12 | 1.28 | 0.06 |

| GPT-3.5 + InternLM-XC2 | 0.14 | 2.20 | 1.46 |

| GPT-4V | 0.44 | 2.60 | 2.46 |

| Qwen2.5-VL | 0.52 | 2.68 | 2.28 |

| Proposed models: Planner LM + VQA model + Reasoner LM | |||

| Mathstral-7B + InternLM-VL-7B + Mathstral-7B | 0.10 | 1.40 | 1.18 |

| Qwen 2.5-Chat-7B + Qwen 2.5-VL-Chat + Qwen 2.5-Chat-7B | 0.34 | 3.08 | 2.46 |

| GPT-3.5-Turbo + GPT-4o-VQA + GPT-3.5-Turbo | 0.16 | 2.66 | 2.62 |

| GPT-4o text + GPT-4o vision + GPT-4o text | 0.40 | 4.00 | 2.86 |

Table 4: Overall Accuracy, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) Reasoning, and CoT Description scores for unimodal text baselines, competitive multimodal baselines, and proposed planner–VQA–reasoner pipelines.

Results

Brief Discussion

The full GPT-4o pipeline achieves the best Chain-of-Thought (CoT) scores (4.00 reasoning, 2.86 description) and ranks second in accuracy.

Our Qwen→Qwen setup is the strongest open-weights alternative, trailing GPT-4o by 6 percentage points in accuracy but matching its description quality.

Mathstral → InternLM underperforms, confirming that stronger vision is required on this dataset.

Clarification on Dev

Dev refers to a 200-problem subset of MathVerse that we created for validation: 100 items are free-form questions and 100 are multiple-choice. The result table shown in the Proposed Model section is the overall average. The Analysis section breaks the metrics down by these two question types.

Analysis

For detailed analysis including intrinsic metrics, qualitative examples, and comprehensive error analysis, please refer to the complete Technical Report (PDF).

The technical report includes Chain-of-Thought coherence evaluation, description faithfulness metrics, final-answer accuracy breakdowns, score histograms, and detailed error analysis for each pipeline configuration.

Future Work and Limitations

Limitation

Despite the planner–VQA–reasoner architecture delivering promising overall accuracy, our experiments reveal four systemic failure modes that currently cap its performance.

Meaningful Queries, Poor VQA Answers

The planner reliably produces semantically relevant follow-up questions, yet the vision–question–answering (VQA) module often supplies incorrect or low-confidence responses. The mismatch is most severe for fine-grained spatial cues—e.g. tick-mark counts or colour-coded labels—where a single pixel error flips the truth value.

Hallucinated Geometric Relationships

The VQA model frequently conflates inscribed with central angles, mistakes perpendicular distances for radii, and misidentifies baselines in composite diagrams. These hallucinations enter the pipeline as false facts and propagate into the reasoner, which then delivers logically impeccable—but factually wrong—proofs.

Absence of Memory & Contradiction Resolution

Answered questions are merely appended to the next prompt; no mechanism detects redundancy or inconsistency. Consequently, mutually conflicting facts accumulate, degrading the quality of downstream reasoning.

Dataset Gaps and Incomplete Ground Truth

Several ground-truth image annotations omit implicit geometric constraints such as "horizontal" or "equal length." Fine-tuning on these partial labels teaches the model to ignore useful cues and occasionally penalises otherwise correct, more detailed descriptions.

Chat–API Deployment Discrepancy

Outputs obtained via the GPT-4o API are noticeably noisier than those observed in the interactive chat window, indicating that our prompting and alignment choices do not yet transfer cleanly across interfaces.

Taken together, these limitations show that the pipeline neither ensures long-range factual consistency nor robustly grounds symbolic reasoning in accurate vision features. They motivate future work on memory-aware retrieval, adaptive query stopping, targeted VQA fine-tuning, and systematic dataset re-annotation.

Future Work

Memory-Aware Retrieval

We will build a lightweight memory module that stores every Q–A pair in a structured buffer and exposes read / write APIs to the planner. The planner can then retrieve, update, or discard facts—eliminating redundant inquiries and resolving contradictions before they corrupt downstream reasoning.

Adaptive Query Stopping

By monitoring the entropy of the VQA logit distribution (or another uncertainty proxy), the system will halt question generation once the marginal information gain falls below a preset threshold. This rule reduces inference cost and prevents the pipeline from drowning in low-value, noisy queries.

Closing the Chat–API Gap via Targeted Fine-Tuning

We observe that GPT-4o API calls yield noisier VQA answers than the interactive chat window. To bridge this gap we will fine-tune the VQA backbone on a re-annotated dataset that zooms into salient regions, crops irrelevant clutter, and adds explicit tags for angles, lengths, and parallelism—aligning the model's visual grounding with the planner's expectations.

Prompt-Refinement Loop

Before a query reaches the VQA stage, a language model will rewrite it for clarity and geometric specificity, discouraging heuristic shortcuts and encouraging attention to subtle spatial cues. The loop iterates until the refined prompt meets a quality threshold or the adaptive-stopping criterion is triggered.

These upgrades directly target the weaknesses identified in our limitation analysis—improving perceptual accuracy, enforcing factual consistency, and enhancing robustness across deployment interfaces.

Ethical Concerns and Considerations

Our system raises two primary ethical risks.

Misleading Outputs (Educational Fairness)

Errors in the perception stage—e.g., mis-reading a diagram's center or angle—can propagate through the chain-of-thought and yield confident yet incorrect answers. If adopted uncritically for homework assistance or automated grading, such mistakes could misinform students and skew assessments.

Mitigation:

Integrate automatic contradiction checks within the belief-state; expose a confidence score and key intermediate descriptions so instructors can spot-check results before trusting them.

Representation Bias

MathVerse mainly contains clean, English-annotated diagrams; hand-drawn sketches and non-Latin labels are under-represented. Consequently, performance may degrade on these styles, disadvantaging certain learner groups.

Mitigation:

Expand evaluation with multilingual and hand-drawn diagrams, fine-tune on that data, and publicly document known blind spots to avoid over-promising performance.

By embedding these safeguards and transparently reporting limitations, we aim to reduce harm and enable safer deployment of multimodal geometry-reasoning systems in educational and related contexts.